Recalling Chancery Lane

By Mike Crean

Churches were dotted around Christchurch by the mid 20th century. But Bishop E Joyce had long dreamed of one more. A small central-city chapel would be a wonderful thing, he thought. And it was — but it lasted only until the major earthquake struck in 2011.

Bishop Joyce drove the establishment of the chapel vigorously. He said it was necessary for people living in the inner-city who had long walks to the nearest churches. He thought visitors to Christchurch staying in central hotels would be pleased with it, as would shoppers from all over Canterbury, and workers in the area who liked to take a walk in their lunch hour. The chapel would, and did, fulfil the ideals of a small community church for locals and a “drop-in” centre for all sorts.

The Bishop purchased land on the corner of Gloucester Street and Chancery Lane in 1956. Chancery Lane was a pedestrian path running northwards from Cathedral Square’s north-west quarter. (The site of the chapel is now beneath the southern point of Te Pae, the Convention Centre.)

The Bishop announced his plan to all parishes in May 1957, 100 years since the first Mass was celebrated in Christchurch, by missionary priest Fr J Petitjean. The bishop chose the name of Holy Cross Chapel.

An appeal for funds to develop the chapel went to all parishes in the Christchurch Diocese. Response to the appeal was great. It needed to be. The chapel sanctuary was graced by marble enhancements from Australia, Italian mosaics, and valuable statues and pictures.

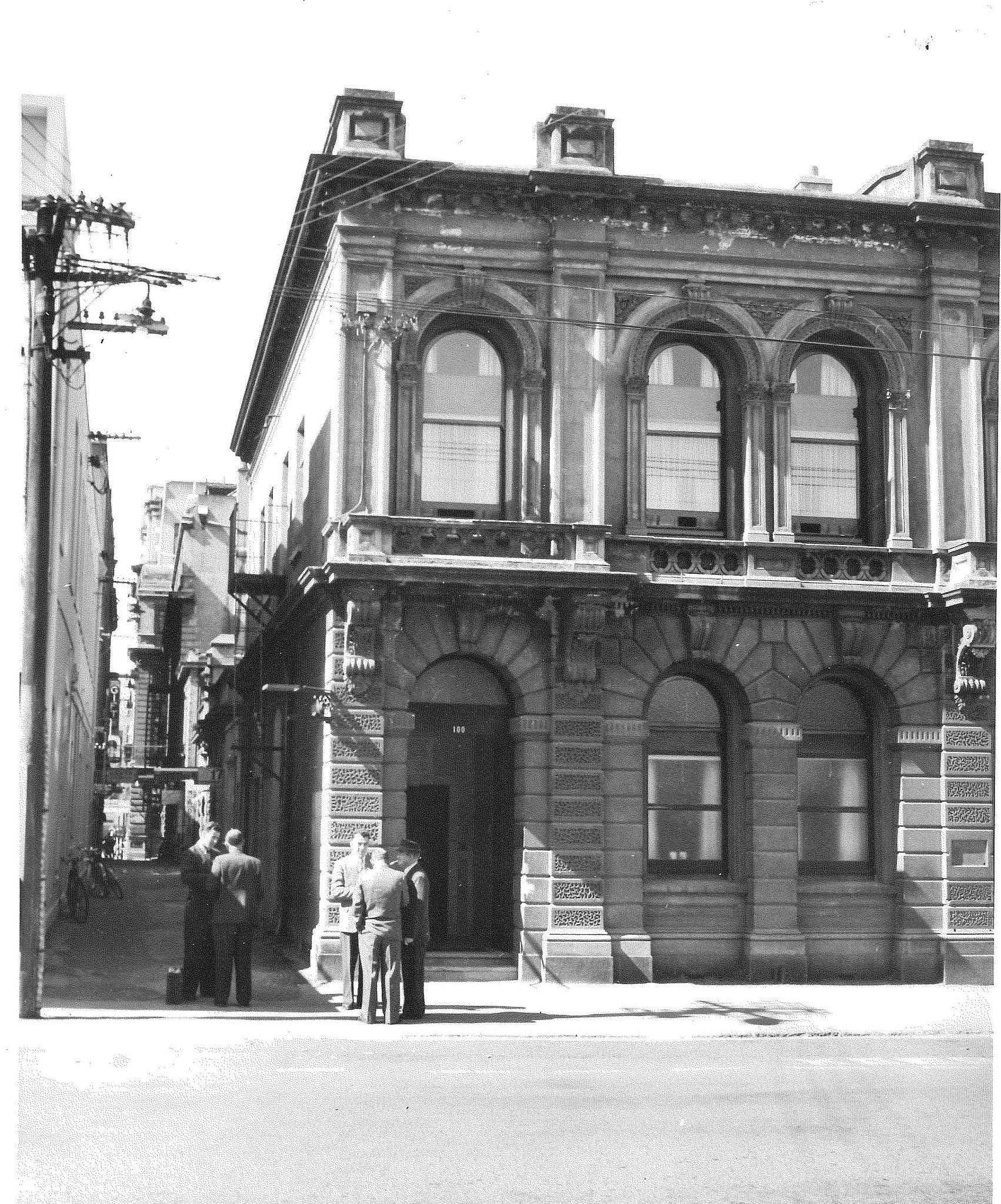

The chapel opened in 1958. The building, previously occupied by offices of the National Airways Corporation (NAC), was of two storeys. The church on the ground floor could seat 80 people. The floor above had separate residences for a priest and a housekeeper.

Fr Tom Liddy, who had been a keen adviser and helper to the bishop, was the first priest of the chapel. For the next 26 years the chapel was very popular.

In one way it acted as a parish church, with a regular community of worshippers attending. In another, it hosted frequent visitors popping in to pray, to catch a Mass, to go to confession, to seek help from the priest, or just to soak in the good feelings and artistic beauty.

In 1984 the chapel moved, not far, just a few metres along Chancery Lane. Developers bought the chapel’s original site and demolished it (and other buildings in the block). The new chapel was moved to a two-year-old concrete complex. Diocesan officers pushed a hard bargain and gained a blessed outcome. They took a lease on the new chapel building for 999 years at an annual rent of $1. The agreement included the Catholic Bishop of Christchurch Diocese being the registered proprietor. In exchange the Bishop handed over the first chapel site to a large company for part of $2.5 million in developments in the lane.

A Catholic shop operated beside the chapel, selling many sacred items. The shop later moved to the end of a new building, adjacent to St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral on Manchester Street. The chapel’s other neighbours included a “magic” shop, a tavern, and a night club. All of these, plus the chapel, and others, were hit badly by earthquakes in 2010 and 2011. All the buildings in the newly renamed Chancery Arcade were damaged, some beyond repair. So, the chapel was demolished in March, 2015.

Demolished but not forgotten

A prominent long-time attendant at the chapel was artist Peb Simmons, now deceased. Her written records of how the chapel community functioned between 1970 and 1990 are in the files of the Catholic Diocese of Christchurch Archives. Simmons notes a community similar to a parish, with prayer groups, a music group, youth group, children’s group, hospital visiting group, a pastoral team, a “core” group, and others. She tells how the chapel community became “a real centre for people involved in Charismatic Renewal.”

Among many events held were picnics and social evenings. Being like a parish, the community held First Communion days, Baptisms, Confirmations, weddings, funerals, and retreats. The chapel community grew so large that members soon outnumbered seats. The congregation moved to a bigger hall, and to yet another with more space.

While Eucharistic Adoration remained most important, the chapel “became the gathering place for visitors, waifs, and strangers from the inner city,” and others, Simmons writes. She also notes the long-serving priests who took part in all the activities. With them, the Core Group worked “to support and exhort.” That’s pretty much what Bishop Joyce would have wanted.